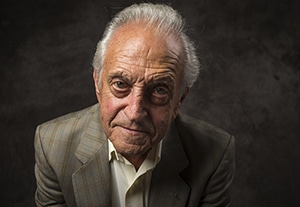

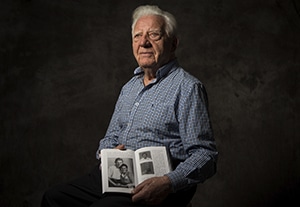

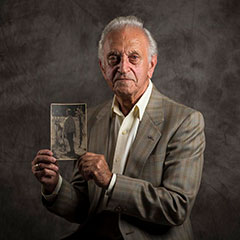

Oscar David Benedikt

“I survived two ghettos, three concentration camps, and a 10-day death march at the end. These are my credentials.

I was a spoiled only child. I mention this because of the tragic contrast with what lay ahead.

In 1939, Czechoslovakia was occupied by the Nazis. Jewish students were thrown out of schools and universities; trainloads of Jews were later deported to Theresienstadt. In 1942, 1,000 Jews were sent by train to Riga, Latvia, without food or water for five days; 80 young males were selected, and the rest of the Jews killed by engine fumes from exhaust pipes fed into the vans. This was how my parents, both aged 49, perished.

In Riga, ghetto food rations were miserable but community life was organized. Young people could be educated. I took courses in Jewish and Zionist history. I was sent to the harbour, offloading 12 hours a day, carrying 80kg bags of grain on my shoulders. In 1944, with the Russian advance coming closer, the ghetto was liquidated. We were taken to Kaiserwald and then Stutthof concentration camp. We could hear the Russian artillery.

In February 1945, I went with the non-Jewish Poles on a death march, with only a loaf of bread to eat. Stragglers were shot in the ditches. I lost consciousness. Two days later I woke to see our liberation. People roamed the countryside collecting survivors and treating them for whatever ailed them. One third of those liberated didn’t make it.

In 1946, my wife and I arrived in Australia thanks to Mr Arthur Calwell, the Immigration Minister who let many survivors into the country. I have never been back to Europe… it is the graveyard of my people.

I speak because when we are all gone, the deniers will still be around.”

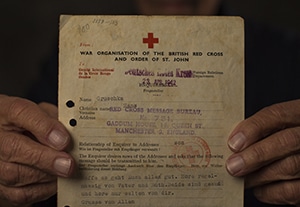

David had no objects, but he shared an insight into the inevitable process of ageing: “There are so many horrible Holocaust memories I try not to remember, and so many good things I now can’t recall.”

David passed away in May 2019.

Oscar David Benedikt

“I survived two ghettos, three concentration camps, and a 10-day death march at the end. These are my credentials.

I was a spoiled only child. I mention this because of the tragic contrast with what lay ahead.

In 1939, Czechoslovakia was occupied by the Nazis. Jewish students were thrown out of schools and universities; trainloads of Jews were later deported to Theresienstadt. In 1942, 1,000 Jews were sent by train to Riga, Latvia, without food or water for five days; 80 young males were selected, and the rest of the Jews killed by engine fumes from exhaust pipes fed into the vans. This was how my parents, both aged 49, perished.

In Riga, ghetto food rations were miserable but community life was organized. Young people could be educated. I took courses in Jewish and Zionist history. I was sent to the harbour, offloading 12 hours a day, carrying 80kg bags of grain on my shoulders. In 1944, with the Russian advance coming closer, the ghetto was liquidated. We were taken to Kaiserwald and then Stutthof concentration camp. We could hear the Russian artillery.

In February 1945, I went with the non-Jewish Poles on a death march, with only a loaf of bread to eat. Stragglers were shot in the ditches. I lost consciousness. Two days later I woke to see our liberation. People roamed the countryside collecting survivors and treating them for whatever ailed them. One third of those liberated didn’t make it.

In 1946, my wife and I arrived in Australia thanks to Mr Arthur Calwell, the Immigration Minister who let many survivors into the country. I have never been back to Europe… it is the graveyard of my people.

I speak because when we are all gone, the deniers will still be around.”

David had no objects, but he shared an insight into the inevitable process of ageing: “There are so many horrible Holocaust memories I try not to remember, and so many good things I now can’t recall.”

David passed away in May 2019.